Policing and Gentrification

This article was originally published May 24, 2018, at the height of the #NoCopAcademy campaign. ATU continues to stand in solidarity with #NoCopAcademy organizers, as well as with working toward the defunding of the Chicago Police department and towards abolition of police and the carceral state everywhere.

The headlines and our social media feeds have been flush with stories of “concerned” white people calling the police on their black neighbors: the Oakland BBQ tattle-tale, the nosy Airbnb neighbor, and the Yale student distressed by her napping classmate, to name a few of the most prominent.

Credit: Monica Trinidad of Chicago’s For the People artists collective.

In these cases, the white neighbors’ “community watch” ethic wasted a few hours of their victims’ time. But time and again we’ve seen police escalate these types of situations to physical violence. It’s easy to focus in on these viral incidents as unique, but we know that this treatment of people of color and the happy collaboration of many of their neighbors is far from exceptional, especially in gentrifying neighborhoods — and can be deadly.

The police — and those happy to call them at every turn — are part of the engine that drives gentrification and, ultimately, displacement. We see this happening in Chicago and all across the country. In light of these stories, the recent organizing of #NoCopAcademy, and the conditions in our own gentrifying neighborhood, ATU has been thinking about how policing plays a role in our struggles.

The Risks the Police Pose

San Francisco’s Anti-Eviction Mapping Project documented a dramatic increase in arrests and citations for petty misdemeanors in gentrifying black and brown neighborhoods. In the Mission, a historically Latinx neighborhood, 311 complaints about minor infractions increased by 291 percent from 2009 to 2014 as wealthy techies moved in.

These complaints can have life-threatening consequences for vulnerable people. Earlier this year, lifelong resident Saheed Vassell was murdered by police in NYC’s gentrifying Crown Heights. Neighbors say it was well-known that Vassell, a 34 year old black man, struggled with mental illness, but that he “wouldn’t hurt a fly.” After 911 calls reported a man pointing a silver object at people on the street that turned out to be a metal shower head, officers fatally shot Vassell. Longtime residents who had known Vassell for years would not have called the police. Police swooped in with excessive force to “protect” transplants at the expense of the existing community.

A “We Call Police” sign previously available for pickup at the 33rd Ward office and for download on the office’s website during Deb Mell’s tenure, with instructions to “put in the windows of your home or business” and “CALL your neighbors and 9–1–1” in case of “suspicious activity.”

Contact with the police also puts residents at risk for deportation through carve-outs in the sanctuary ordinance, which ensures that police do not cooperate with ICE. One of these carve outs include being present on the gang database, a controversial database used by Chicago Police Department that has been heavily criticized for its inaccuracy. When gentrifiers constantly call 911 to complain about loitering and other minor “offenses,” it gives police the opportunity to add people to the gang database, for which they do not need to provide any justification or notice. Once added to the database, those listed are exempt from the sanctuary ordinance and their info can be handed over to ICE.

Increased ICE presence also gives landlords leverage over their tenants (like by threatening to report them to immigration). When homeowners, landlords and developers have an interest in driving undocumented immigrants out of a neighborhood to increase property values, gentrification and violent immigration enforcement reinforce one another.

“Cleaning up” the neighborhood

Often calls for increased policing come under the guise of “cleaning up” a neighborhood’s image, but actually work to increase property values at the expense of low-income residents of color.

Albany Park residents outside Deb Mell’s office urging the Alderman to vote “no” on the $95 million Cop Academy. Mell brushed them off, voted yes anyway, and recently even celebrated her approved requested for increased police presence in her neighborhood.

In Albany Park, 33rd Ward Alderman Deb Mell organized a “Community Safety Meeting” in February 2018 in response to “constant public safety concerns” her office receives from the neighboring community regarding the Interstate Blood Bank.

The Blood Bank has sat on a busy corner in the heart of Albany Park for over 30 years, and attracts a regular clientele of low-income Chicagoans who donate plasma for money. At the meeting, the attendees — largely white and property-owning, despite the fact that Albany Park is majority non-white and renter — used coded racial language to portray the Blood Bank’s clientele as a shameful presence that makes the neighborhood look bad. Although their few legitimate concerns, such as improper disposal of biohazardous trash, were the fault of employees, people focused their complaints on the clientele and their friends who wait for them outside on the street, playing music and talking. Some claimed the clientele were involved in drug dealing without evidence.

Attendees referred to their property-owning status as if it gave them special, if not exclusive, right to comment on the situation. No mention of how the clientele are selling their blood for a pittance to get by.

A few attendees mentioned they had come out to ATU-organized actions to support tenants going through an eviction on the block last year, as though this support immunized them from racial bias or gentrifying behavior. Increased police and security presence at the Blood Bank will no doubt harm not only the clientele, but also neighborhood residents of color who live nearby. It would likely make the same immigrant residents that attendees were proud of supporting earlier feel unwelcome on their own block.

The Neighborhood Watch

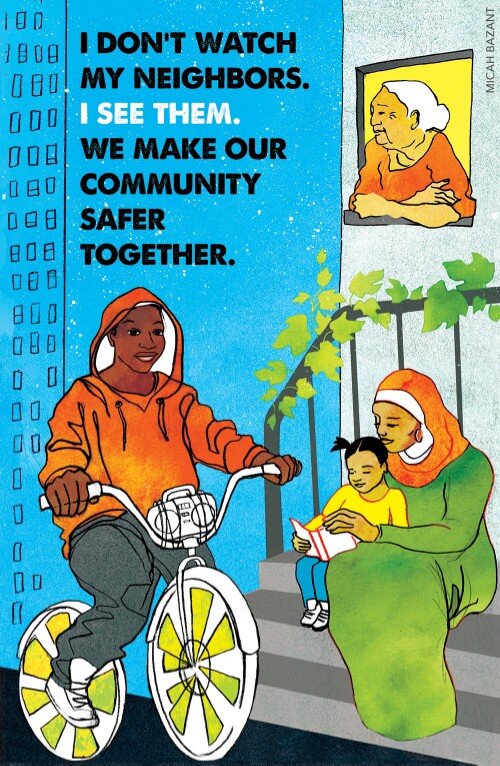

Poster designed by Micah Bazant with the Ella Baker Center for the Night Out for Safety and Democracy event.

Homeowners in gentrifying communities are encouraged to use the police to push out low income tenants, immigrants and people of color. This can be seen in neighborhood watch groups that collude with the police to target “suspicious activity” — racial and class profiling. In this way, the police pit neighbors against each other by putting power in the hands of a few to determine what behavior is disruptive or dangerous. The result is a community that watches one another as opposed to watching out for each other.

The latter is what ATU believes in. If we have to live with ICE and CPD on our streets, they need to be monitored closely by the community, and those for whom the police pose a less immediate threat need to support and look out for neighbors that may be at risk.

Police concentration in low-income communities of color speeds up gentrification by causing financial hardship in the form of citation fines, making people of color targets in their own neighborhoods, and by forcibly removing poor community members in the case of cash bond while awaiting trial. And of course, the criminal justice system so often does landlords’ dirty work for them: it is the police, after all, that enforce eviction orders. The faith that society has in the police comes from their faith in the legal system, and the idea that we need laws in order to live safely.

ATU does not think all rules are unjust, but as we see unjust yet fully legal acts carried out by property owners daily, we have little faith that the legal system, and police as a whole, are here to protect the working class, immigrants, and people of color in our neighborhood.